Some disasters don’t arrive with a bang. They come slowly, like a shadow stretching over decades, unnoticed until the day we wake up and realize the damage cannot be undone. Land in Kenya is becoming one of those slow-burn national crises and it’s unfolding right before our eyes.

We must start by making one thing painfully clear: land is not the same as real estate. For years, politicians, speculators, and middle-class dreamers have blurred the two, thinking that buying a small plot automatically means economic value. One day, a government will take office and have to face the brutal truth , that we no longer have land that feeds us, nor real estate that shelters us. And when that day comes, the actions taken will cut deep.

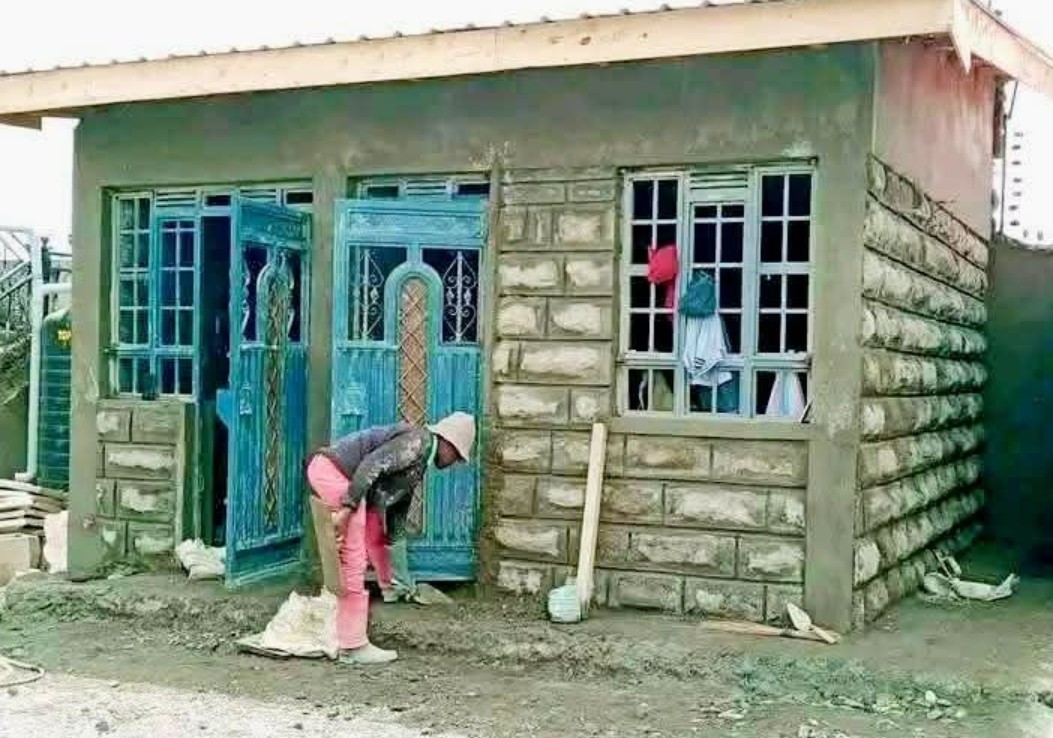

Here’s how it’s been happening. Large companies, sometimes fronted by friendly brokers, approach ancestral landholders often poor farming families worn down by years of unpredictable rains, poor markets, and hard work with little to show for it. These families, tired and hungry for change, sell off ten or twenty acres for what feels like a small fortune. The companies quickly slice the land into 50-by-100-foot plots and market them to Kenya’s middle class. Buyers, armed with payslips and ambition, rush to own “a piece of the future.”

But here’s the truth nobody says out loud: over 90% of these plots will remain empty for decades. They are not homes. They are not farms. They are symbols ,proof of status, something to talk about at a pub : “I have three-quarters in Kamulu.” These parcels are visited maybe once a year, a dusty Premio or Mazda parking briefly by the fence to “check the land,” before disappearing again for another twelve months.

Fast forward twenty years. Kenya’s agriculture will have withered, not because of climate alone, but because fertile land was chopped into fragments too small to sustain meaningful production. Real estate will have failed too, because there will be no coherent development ,just scattered plots, fenced and idle.

One day a new sane government will come to power, and commission studies to understand why food imports have overtaken local production, why wheat, maize, and vegetables cost more than ever.

The report will be blunt: those countless 50-by-100 plots have no real economic value. They are dead space on the map. And so, land consolidation will begin. Plot owners will be forced into collective schemes ,1,000-acre estates leased or sold to corporate farmers, some from overseas.

Picture yourself at 70, standing with your son at the edge of one such estate. Far off, maybe 10 kilometers away, a combine harvester crawls across the horizon. Your son squints and asks, “Is that a harvester or a rock?” You’ll tell him, “you see where that harvester is ? . Somewhere there, we own a 50-by-100 and we get dividend every year ”

And if we don’t get a leader brave enough to push through serious land reforms, you won’t even be there to tell the story. The shape and nature of our country will be unrecognizable , a patchwork of wasted plots and broken farms, feeding no one. The elite will have fled, seeking asylum in safer nations, far from the fury they helped create. But the rest will remain, trapped in a land they can no longer till, watching food prices climb beyond reach.

The next conflict in Africa will be driven by food scarcity and exacerbated by population explosion. Two things we are not interested in addressing .